Members Area

Unfortunately our cinematographers do not have time to address individual questions but there is a myriad of material on the web and Vimeos and interviews which you can search for which should answer your questions.

See: Role of Camera Operator.

If you are coming straight from school, you will be looking to find a film-making degree that suits your particular strengths and skills. Courses vary between highly academic film courses such as the one at Warwick, which teach film theory as an intellectual pursuit, much as you might study English literature; they are clearly valid, but offer little if any practical experience of the film-making process. Practice based courses swing the balance the other way so as to offer a predominantly hands on experience with a little bit of theory on the side.

So how to choose an undergraduate course? There are probably something upward of two to three hundred BA courses in some flavour or other of ‘Time Based Media’, (i.e. Film). The best ones are taught by practitioners who have extensive industry experience coupled with the teaching skills to impart the knowledge they have accumulated while working in the film business. If you can be taught by a BSC cinematographer, then great! Be aware that at BA level, there are no specific cinematography courses so you should be looking for a Film Production Degree that has a strong cinematography pathway, again with an experienced DP amongst the teaching staff.

Have a look at the equipment available to students. Does it allow for interchangeable lenses, so as to mimic professional practice? Is there a dolly and track so it is possible to move the camera smoothly? Lighting is a key skill for a new cinematographer to master, are there film lights with both tungsten and daylight colour temperature? Are there flags, reflectors and trace frames to be able to learn to control the light? Another important consideration is to see if the equipment is available to students outside of the course work so they can explore and learn on their own.

But at this stage don’t be over concerned if the equipment available is not the most up to date professional kit. Cameras become obsolete very quickly and film courses are expensive to run, it is more important to have good tutors than the very latest kit. However the camera kit should really have file based capture rather than tape. 16mm and 35mm film remain the most brilliant teaching tools, if you can find a course that has an element of film while it is still practicable so much the better.

In the UK most Universities are state funded, with a small number of private colleges which are accredited to bestow degrees existing alongside. Fees at the main Universities tend to be lower, but for the good ones, entry requirements can be quite onerous. A good test of how good a course is perceived to be is whether the course has to recruit or is able to select from many applicants.

If you are just leaving school and you are really very academic, expecting top end grades at A level, you should consider doing a degree in English or another of the Humanities, at the best academic University you can achieve. While there be involved in film-making and prepare a portfolio with a view to achieving entrance to a good MA in Cinematography. This will allow you the greatest degree of flexibility in your future career.

The number of Post Graduate courses in cinematography is increasing. The flagship course is the oldest MA in the UK at the National Film and Television School at Beaconsfield. This course is accredited by the Royal College of Art, and offers eight places a year chosen from many hundreds of applicants. Other courses should be appraised in a similar way to the BA courses listed above. As these are specialist cinematography courses you should place a greater emphasis on studio space, equipment and the quality and practical experience of the lecturers. Particularly at MA level the relationships students build at college with directors and producers often continue into professional life.

Finally, it should be noted that the traditional ways into the industry, of learning your craft in an equipment house and moving up through camera assisting roles on set can still apply.

Camera manufacturers such as ARRI and Panavision offer training situations in house as do many other camera and lighting rental companies and it is a useful way to ensure you develop the necessary skills to familiarise yourself with camera and lighting equipment. Working with these companies will also allow you to meet camera crews who might be in a position to help you move forward onto the set in the industry.

There are many great DPs who never went to college, who learnt by watching and working with great cinematographers as part of their teams.

Creative Skillset also offer work opportunities in the industry so it is worth keeping an eye on their website at https://creativeskillset.org/

Please note that the BSC do not offer work experience with their cinematographers, most trainee positions arise from the recommendations of focus pullers and clapper loaders, (1st and 2nd Assistant Camera).

Nic Morris BSC is a Director of Photography with extensive Feature Film, TV Drama and Commercials credits, and has been nominated for the BSC Best Cinematography (Theatrical Release) award. He has been running a parallel career in academia for over twenty years in an attempt to create a work-life balance. He has taught at the NFTS and written and led both BA and MA film production and cinematography courses at other Universities, and is currently also an External Examiner.

June 2016

The Trainee position has become an extended member of the camera team, and as such a certain level of familiarity with on set practice and professional camera systems is becoming the norm. There are several courses for Camera Trainees which do offer placements on production. The Guild of British Camera Technicians runs short courses from time to time for camera trainees and camera crew http://www.gbct.org. Nowadays most, but not all trainees are film course graduates. Trainees are recommended to the DP by the camera assistants so making contact with them is a good first step. Skillset is also worth contacting for advice as they run placements from time to time, http://www.creativeskillset.org/.

All approaches to Cinematographers can be made via their Agents, these are listed on the individual cinematographers page.

The BSC office having been asked which was the first commercial film (either silent or sound) to use the term Director of Photography passed the conundrum to erstwhile Governor Phil Méheux for elucidation. As there is nothing currently on the world web on the subject, Phil undertook exhaustive research via YouTube and IMDb to discover the following. If you have any input or comment please do let us know.

THE FIRST COMMERCIAL FILM TO USE THE TERM DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

by Phil Méheux BSC

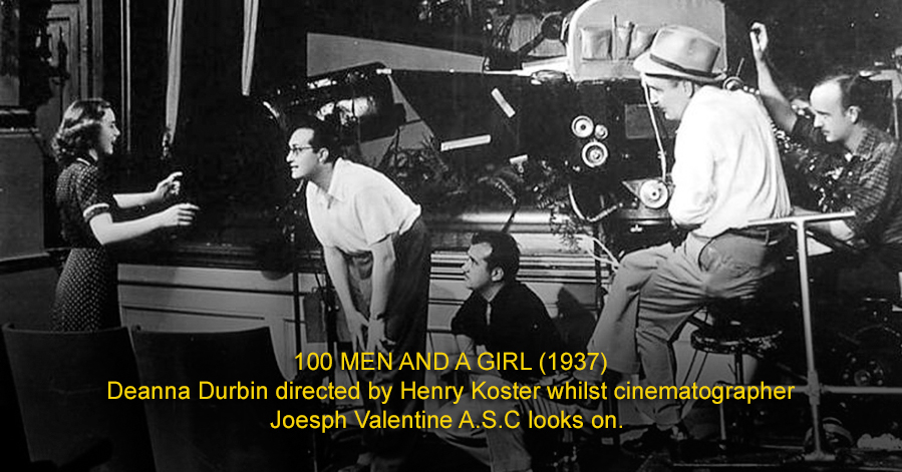

to be given on the Universal Picture: ONE HUNDRED MEN AND A GIRL, released in 1937, starring Deanna Durbin and Leopold Stokowski, to cinematographer Joseph Valentine ASC (Picture on the heading). Here is the screen credit:

As stated above there is no article on the web or in any manual that deals with this issue. I have also spoken with the President of the American Society of Cinematographers and he has no archive on this subject. My article which follows deals mostly with the development of cinematography with major feature films of HOLLYWOOD.

In the early days of cinema, there was generally only one cameraman who worked without an assistant, hand cranking the camera and very often developing and editing the footage. Probably the best known of these American pioneers was Billy Bitzer who famously worked with D. W. Griffith on BIRTH OF A NATION (1915), etc. Bitzer began work as a motion picture cameraman in 1896. Another well known name was Roland Totheroh, Charlie Chaplin’s personal cameraman. Images from both these artists still survive to this day! At that time, most films were 200 feet in length and at varying speeds mostly between 12 f.p.s. to 18 f.p.s. or even outside these numbers. There was no standard speed then.

Caption: “Billy Bitzer with his Pathé Camera and D. W. Griffith on WAY DOWN EAST (1920)

When foreign markets became important it was common to run a second camera with a separate operator alongside the main camera for a second negative. Further developments allowed the use of an electric motor, which freed the hands of the cameraman to adjust focus or pan and tilt the camera. Then along with panchromatic film came sophisticated artificial lights allowing more dramatic use of light and shade followed by Technicolor which usually involved 2 cinematographers and a very slow stock, so you can see as the industry progressed the responsibilities of the cameraman were increasing.

The advent of sound brought in a standard frame speed and cameras that needed to be silent. They often had to shoot “live” with multiple cameras for musical films because a method of cutting the sound track and hence the music, had not been perfected. Cameras had to be stationed inside sound-proof boxes which were naturally airless and stiflingly hot and known contrarily at the time as “iceboxes” because they resembled large refrigerators. This meant the cameraman could no longer be the sole cameraman. Now, he had to have several operators and it’s possible that the term “Director of Photography” grew from that but I have no confirmation of this and in fact some of the most famous musical films of those early years, BROADWAY MELODY (1929), was the first film to be credited as “all- singing, all-talking, all-dancing” and carried the credit “photographed by”. The first sound film with dialogue, as we know was the JAZZ SINGER (1927) “photography Hal Mohr” using only one camera but the first appearance of the term DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY appears to be 9 years later.

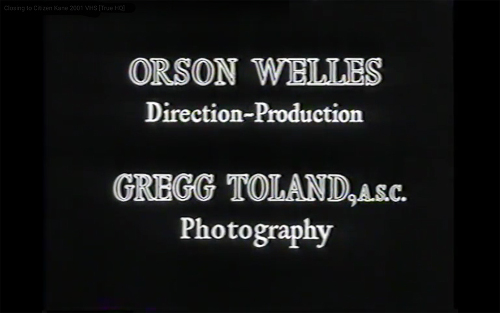

Looking at the credits for important movies after the invention of sound using the unreliable IMDb as a source with YouTube as a follow-up, the earliest screen credit I could find with the words ‘DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY” appears to be given on the Universal Picture: ONE HUNDRED MEN AND A GIRL, released in 1937, starring Deanna Durbin and Leopold Stokowski, to cinematographer Joseph Valentine ASC (Pictured on the heading). Here is the screen credit:

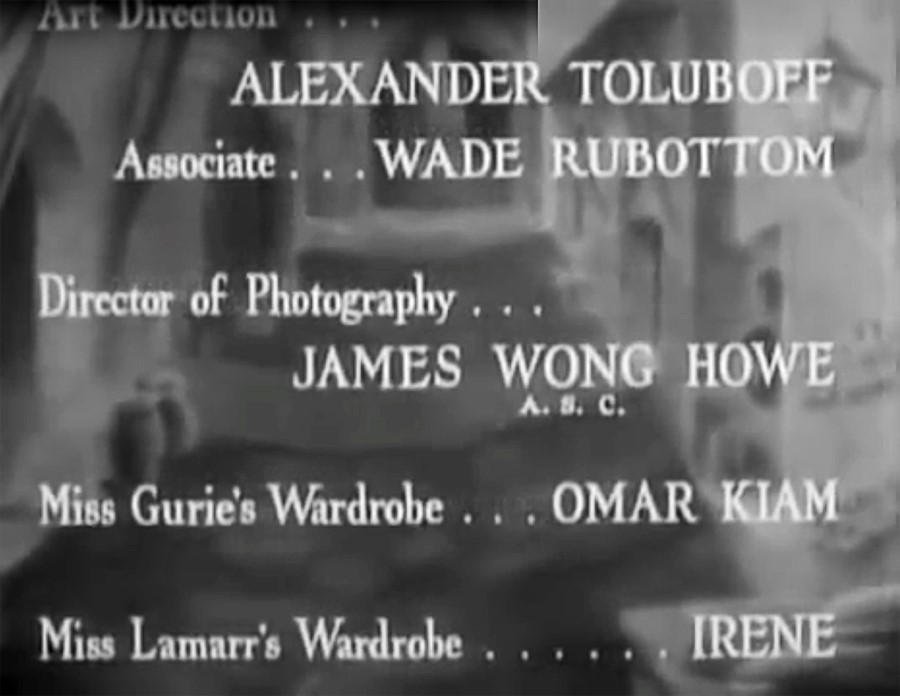

The story of the film required significant footage of the Philadelphia Orchestra and close-ups of musicians no doubt using multiple cameras which may have contributed. From that film onwards, Valentine was always credited as “Director of Photography.” How this came about is not documented and I did not find any other instances before this movie nor amongst contemporary films of that year. The next appearance of the term for a different cameraman was not until the 1938 film ALGIERS for James Wong Howe ASC directed by John Cromwell and starring Charles Boyer, Sigrid Gurie, and Hedy Lamarr. Although his subsequent use of the term was initially sporadic.

It is my contention and only mine that many of the cameramen of those times who were under contract to a major studio were not necessarily given a choice of credit because the studio controlled credits whereas today and possibly then, a cameraman who was freelance or not attached to one studio (Joseph Valentine and James Wong Howe for instance), might have been able to state his preferred credit in his contract. It could also be linked to membership of the American Society of Cinematographers, because you will notice that all the credits I have captured have the initials “A.S.C." after the name which was not common for studio pictures.

[It is also worth considering that the studio cameramen in those days often controlled choices of costume, hairstyles, make-up and set design which you could argue made them more of a “director”, however in recent times this no longer appears to be the case. The IATSE union (also known as the International Cinematographers Guild) probably the last remaining motion picture union with any control still has the job title: “Director of Photography”.]

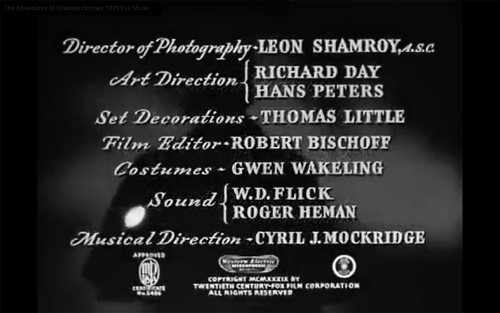

By 1939 the term was used more often. Contrary to the “freelance” theory, studio cameraman par excellence, Leon Shamroy ASC (with 18 Oscar nominations and 4 wins) was a contract cameraman for 20th Century Fox and after THE ADVENTURES OF SHERLOCK HOLMES 1939 (credit below) was always credited with DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY.

Most Hollywood studio pictures of the 20’s, 30’s and 40’s say "photographed by” or “photography” (which I still think is a nice label but of course does not accurately represent moving photography as “cinematographer” does. [It was Léon Guillaume Bouly who in 1892 patented the first device known as the “cinematographe.” A 3-in-1 device to shoot, develop and screen moving pictures.] One of the most revered cameramen of that period, Gregg Toland ASC, freelanced several times away from his contract at the GOLDWYN STUDIOS most famously for CITIZEN KANE in 1941 with one of the most notable credits for a cameraman on the same card as the director and the last card the audience saw and to my knowledge has never been equalled:

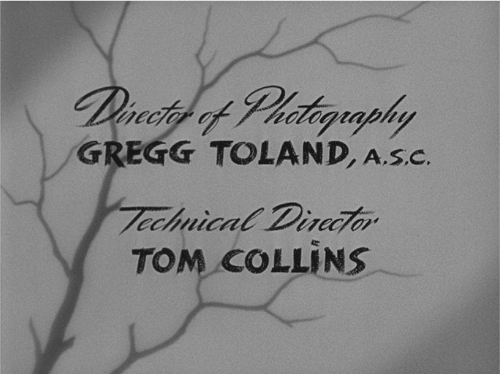

However, this credit appeared on GRAPES OF WRATH (1940) a year earlier when he freelanced for Fox but did not use the term again until 1946 preferring “photographed by”:

The only way to solve this question would be to screen all the releases since 1927 - the advent of talking pictures - good luck!

Nowadays it is almost ‘de rigeur’ that the cameraman on a mainstream feature film will be credited as “Director of Photography” and referred to as a “DP” or “DoP”, a term that is very common amongst the studios of Hollywood. However, the legendary Vittorio Storaro ASC AIC once famously said that the reason he called himself “Cinematographer” and not “Director of Photography” was that he believed there was only one Director on a shoot!

EPILOGUE: One feels that the term should be reserved for cinematographers who have a wealth of experience as the criteria for BSC Full Membership states:

“... the work must demonstrate creativity and an appreciation of the art of cinema and more than just professional competence. Particular attention will be paid to lighting for differing conditions, both interior and exterior, studio and location, and to how composition and camera movement have been used to enhance the story and mood of the piece.”

It is my sad observation nowadays that anyone who can push a button on a digital camera and create a website now credits themselves as DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY - another nail in the coffin for the respect of the DP almost as bad as “A film by ….” which was created by agents to give their director clients more kudos than perhaps they deserve. And I was told by the president of the ASC recently that he was given a business card from an eager young man straight out of film school at one of their ‘open houses’ which read: “Sound - Key Grip - Editor - Director of Photography – Director!” His comment was: “At least we got billed above the director!”

Phil Méheux BSC

This document is reserved for full members and can be obtained by contacting the BSC Office. office@bscine.com

For clarification, on screen credits, publications, promotions and correspondence, the accreditation BSC should be included, after the accredited members name, without full stops, i.e. BSC

For exclusive access to Q&As, Masterclasses, the BSC Expo VIP night and the BSC Short Film Awards

Find out more about the BSC Awards

13-14th February 2026, Battersea Evolution

Find out more about Media Partner